In this article

Executive summary

The language used in a job advert can have a powerful effect on the way male and female applicants perceive the role and their suitability for it. Recent media reports have highlighted how the use of language in ads may be a potentially important factor in gender imbalance in the largely male-dominated tech industry.

In this study, we have analysed the language used in ads for tech jobs to determine what kind of language is used, and whether this might be a significant contributing factor to gender imbalance in the sector. At first glance, the research shows that the majority of tech ads use language which should, in fact, appear more attractive to women than men. However, on further analysis, the picture becomes less clear cut, and we did find evidence that suggests tech ads may be more orientated towards ‘male’ language – especially for higher-paid jobs.

The importance of language in job ads

The words we use matter. That is especially true when it comes to job advertisements. According to one recent study, language used in job adverts can substantially influence the kinds of people who apply for a role. Certain terms appear to attract certain profiles, while other words put off otherwise well-qualified candidates. For example, using a term like ‘manage a team’ seems to deter female applicants from applying. But change the word ‘manage’ to a word like ‘develop’ and many more women apply.

By making small tweaks to the language used in job ads, businesses can potentially draw a wider range of candidates to their ads and expand the possible talent pool. This means they will attract a wider range of valuable staff, and are more likely to hire the best possible candidate.

Today, there is growing recognition in the technology sector that women are under-represented. In Australia, a mere 28% of IT professionals are women. And yet, this is in fact a relatively high proportion of the IT workforce compared to other members of the OECD, a group of 41 wealthy countries (Australia has the second-highest proportion of female tech workers, after Bulgaria). Nevertheless, this represents a serious under-representation of women in tech and consequently a significant under-utilisation of talent.

This report is therefore intended to explore just what level of impact the language used in job ads has on female applicants to tech-sector jobs. We wanted to find out if the language used in ads was potentially discouraging female software developers, technicians and IT support staff from applying for jobs in otherwise fulfilling careers, and so we analysed just under 2,000 job ads to find out.

Context: TechBrain’s values and hiring female tech staff

At TechBrain, our key values include a focus on transparency and a desire to question the status quo. When we first learnt about how language used in job ads can affect the number of male or female candidates who apply for jobs, we wanted to ensure that our ads were not putting otherwise qualified women off applying. In the spirit of transparency, we chose to investigate because our own experience of applications suggested we might be falling foul of this issue. For example, in the past 12 months:

- We posted 11 job ads

- We received 319 applications

- Only 27 (8.5%) of those applicants were women

What’s more, none of the women who did apply had the skills we needed. One third of those applicants had zero IT skills or experience. Others either had insufficient skills/experience, required sponsorship or had a CV that suggested they moved rapidly between jobs (a trait we try to avoid when hiring).

This all suggests that something in our ads was deterring possibly qualified female applicants from applying. Given that we operate in a country where the rate of women in IT roles is 28%, we’d expect at the very least that a quarter of applicants would be women. In fact, we were getting even lower numbers of interested female applicants than that. We can only assume that other tech firms have this issue too.

In order to address the issue of low female applicants, we decided to take three courses of action.

- TechBrain have pledged to provide it’s Human Resources partner, Requisite HR, a 16.4% increase in recruitment budget to assist them in finding a suitably qualified female candidate for their next role. TechBrain chose this figure to draw attention to the fact that the gender pay gap in Australia is an unacceptable 16.4%.

- Having learnt about the impact of language used in ads, we commissioned this report to explore how much of an effect the language used in tech job ads might have.

- Whilst we we offer unlimited annual leave and have employees working part time and on flexible hours we have done a poor job highlighting this in our job adverts. With that in mind we have decided to double down our efforts in this area to ensure that our job adverts, hiring team and website all emphasis this flexibility from the outset to ensure we don’t miss out on applicants who would have applied had they known about the flexibility we offer.

- Understanding that women may undersell themselves and not apply for jobs if they feel they do not meet all the criteria, compared to men who tend to apply regardless, we will simplify our selection criteria, avoid long lists of technical skills and advertise jobs through Expressions of Interest.

By making these pledges, we hope to have an immediate impact on our own workplace culture, as well as contributing towards the conversation around the representation of women in tech and IT roles across the industry we serve.

Bias, recruitment, language and gender in Australian tech roles

There’s a wealth of inspiring women in tech jobs in Australia. These include leading executives in Australian branches of major international tech firms like Microsoft and Twitter, as well as entrepreneurs running homegrown brands. Indeed, at TechBrain, 40% of the decision makers we deal with at our top 20 clients are female.

But, on the flip side, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveals that the number of women in tech has been on the decline since 1990, when there was, in fact, parity between the numbers of men and women in the sector. What’s more, fewer than one in five university students studying an IT subject in Australia are women.

This is surely a loss for the wider economy. Global management consultancy McKinsey & Company’s annual Delivering Through Diversity reports have shown, time and again, that businesses with more diverse a workforce significantly outperform less diverse competitors. This is generally attributed to the fact that having a greater variety of viewpoints facilitates a greater exchange of ideas and allows firms to enter new markets that they may not otherwise have catered to.

At present, Australian IT, and the tech industry on a global scale, is missing out on all the potential benefits of increased gender diversity.

Bias and recruitment

In Australia (as in most developed countries), it is illegal to advertise a job that indicates that the employer intends to discriminate against candidates on the grounds of sex, marital status, pregnancy or potential pregnancy. It is therefore highly unlikely that any technology company would begin an advert with language such as ‘Male programmer wanted’.

Discrimination and bias may still exist and are often much less conspicuous than in the example above. Indeed, the phenomenon known as ‘unconscious bias’, where people make short-cut assumptions about people based on some socially defined factor is extremely common in recruitment. Diversity Australia uses the following definition of unconscious bias:

Unconscious or hidden beliefs – attitudes and biases beyond our regular perceptions of ourselves and others – underlie a great deal of our patterns of behaviour.

Unconscious bias is not necessarily malicious; rather, the human brain has evolved to spot patterns that help it to understand the world quickly. If someone has only ever worked with male software programmers, they may (falsely) assume that it is a job only men can or want to do, so they therefore will unconsciously discount women applicants when hiring because it doesn’t match the mental pattern they hold.

Other factors potentially affecting low-representation of women in tech.

While we believe that bias in the recruiting process and gendered language are potentially contributing factors to the issue of low application numbers and fewer women in technology companies, there are a number of other issues which relate to and contribute to the problem. During the course of our research and conversations with the female leaders, a range of other issues came to light. These included low numbers of female students studying STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), a lack of confidence in applying for technology roles, a lack of female role models and poor flexible working arrangements for mothers and carers. While each of the issues could be the subject of their own report, it’s important to refer to them here to show that bias and gendered language aren’t an issue in isolation.

Low numbers of women studying STEM subjects

In 2018, less than a quarter (24%) of STEM graduates were women. This has two clear implications for the recruiting process and female representation in the industry. Firstly, there would be fewer female applicants for STEM roles. Secondly, that those who did apply might not have sufficient training to be considered for the position (one of the issues we encounter at TechBrain). There are a range of initiatives that firms are now attempting to tackle unconscious bias through training and sponsorship, and the Australian government is actively encouraging more women to enter STEM subjects. By encouraging female students to enter this area, the number of potential applicants will increase.

A lack of confidence in applying for technology roles

There is a theory, as expressed in this article , that women are reluctant to apply for jobs unless they have 100% of the skills required, whereas men are willing to apply if they meet 60% of the criteria. This issue obviously intersects with the issue of women leaving university without the relevant qualifications and experience, but following our conversation with women in the industry, it also applies to the language used in job adverts. Long lists of required skills could be off putting to female applicants who feel they’re not capable and so won’t apply, even if those skills aren’t fundamental to the role.

A lack of female role models in the technology industry

Thanks to popular culture and the fact that many prominent tech companies’ CEO’s are men (think Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, or Tim Cook), many people unconsciously think of IT as a male activity. Clearly, there’s no scientific reason for believing this to be so, yet these stereotypes may count against women who apply for jobs and also dissuade some women from pursuing a career in this sector altogether. However, this issue can one of the women in tech we spoke to about this issue also made it clear that she had plenty of role models, they just weren’t women and their gender didn’t occur to her as deciding factor in her desiras contentious, there are many women operating at a high level in the technology field (although perhaps they don’t have such ready access to the media platforms utilised by men). Added to which, e to pursue that career.

Poor flexible working arrangements

There has been a suggestion that the technology industry doesn’t do enough for mothers (and fathers) in terms of flexible working arrangements and childcare. Some of the women we spoke to agreed on this, particularly in terms of the language used in adverts, recruiters should be signposting what their approach to flexible working is and whether it’s an option. If female applicants aren’t aware that there is flexibility around work hours, then they’re less likely to apply for the job. This had immediate implications for own recruiting process. We operate flexible working hours at TechBrain and many of our roles are full time and part time. However, it’s clear to us that we’re not signposting our flexibility clearly enough, and so we’ve undertaken to change the structure and wording of our job adverts to highlight job flexibility to mothers, fathers and carers.

Views from the industry…

“There is an intrinsic bias in sorting through applications and undertaking interviews. I used to be the “female” panel member at a different company. It was an ongoing challenge to get more women to be shortlisted (or even all women to be shortlisted) if you want to get your numbers up and give more opportunity.

I don’t think this is reverse discrimination at all – we all revert to what we know, and generally look for ‘people like us’ – we need to challenge that and lean on female colleagues to assist with shortlisting and interviews. In terms of flexibility, I always advertise every job role as full time or part time; flexibility is a big part of decision-making.

Using language like – ‘returning to the workforce’; ‘need more flexibility’; ‘want to apply your skills in a collaborative team environment’ may also help. In terms of confidence, it is definitely the case that women will ‘undersell’ and not apply for jobs for which they feel they may not have the requisite skills and experience. Strategies to remedy this issue include: simplifying selection criteria; putting up ‘expressions of interest’ jobs; using better wording around ‘join our team/support and training provided/learn on the job/work with an experienced coach/mentor’ etc. We also try to avoid long lists of technical skills in the belief that women are more likely to want the ‘environment’ to work rather than the tasks on offer.”

Julie Carr, CEO, Early Start Australia

“There’s a lot of research that has found that girls as young as 8 -10 are moving away from science subjects, based on gender stereotypes. Girls at this age (and younger) are just as strong as the boys at science but around grade 5-6, they take on more ‘female’ subjects.

There’s a lot that can be done with the curriculum to attract girls to the science subjects (they’re quite male focussed).

It starts at an early age for girls to see STEM as legitimate careers for them. The primary school workshop I went to recently was a great example of this, where the girls just don’t know what options are available to them. They need to physically see women in the roles to see that they might be plausible for them.”

Alison Atkins, CEO, Acquire Technology

“I believe that young women making career choices are influenced by their teachers and parents. It is my view that early education by dynamic female teachers is essential in providing technology as a career of choice for girls. Whilst salaries in teaching are low compared to the tech industry, this remains difficult. It would be great to see large organisations in the tech industry investing in grants for teaching in order to attract female role models.

Flexible working arrangements for women looking to enter a career or industry are essential. As a working mother, I have chosen pathways where flexibility is assured. Unfortunately, in my experience this has usually meant a lower salary for women and significantly slower pathway to the top. I also find that women are often competing for promotions with men where there are very different levels of support on the home front.

This is a factor often missed by senior management with understanding what true flexibility means. It is not just variable hours, it is understanding outside pressures that impact on mental wellbeing. Any industry that wants to attract women must address these issues.”

Bronwyn Rose, Executive Manager Corporate Services, Town of Mosman Park

How certain language in ads can be perceived as ‘gendered’

The choice of words used in a job ad may seem of little importance when it comes to the gender of the applicant. A typical job ad will include the following kinds of information:

- A job brief, outlining the person’s role

- A list of responsibilities

- A list of essential experiences, skills and qualifications

- Additional desired experiences, skills and qualifications

- Salary information

- Information about the company

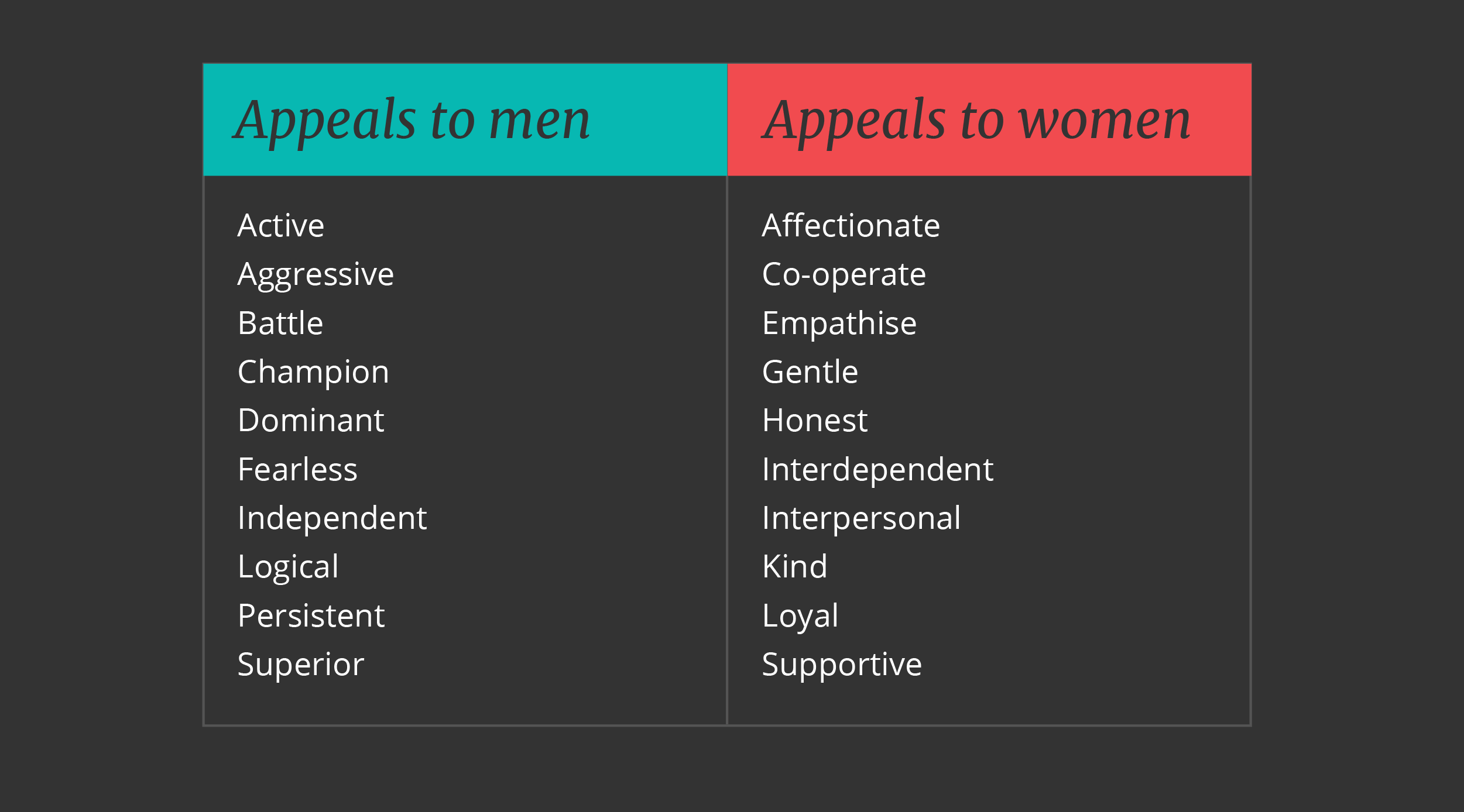

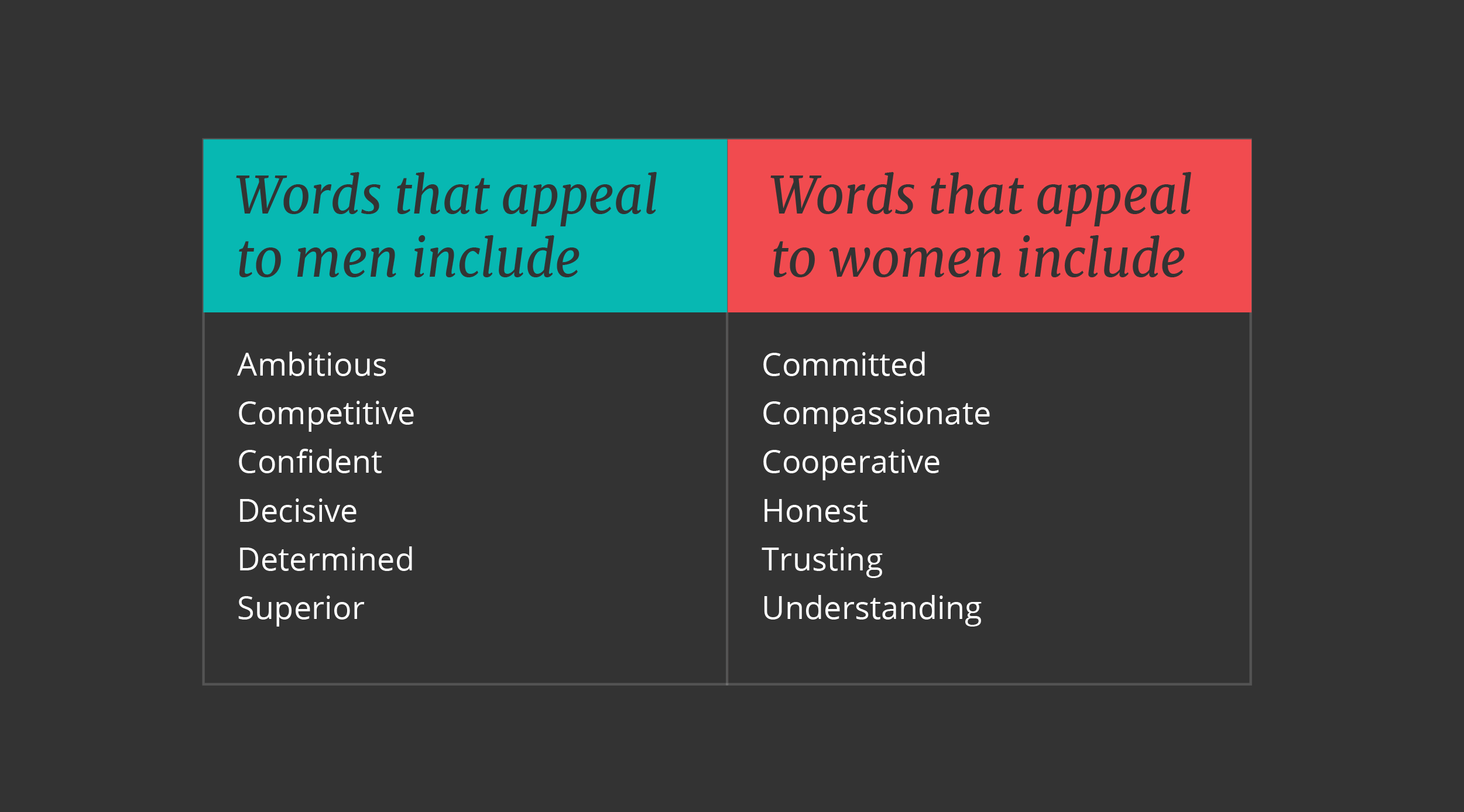

At first glance, it does not seem particularly apparent that the language used in such an ad would appeal more to men or women – an ad is, after all, just a description of tasks, responsibilities and requirements. However, research suggests that certain words are perceived as more attractive by men, whereas others are seen as more appealing to women. When men and women see the kinds of words that appeal to them, they may more readily identify with the job and feel more confident that it is something they could do.

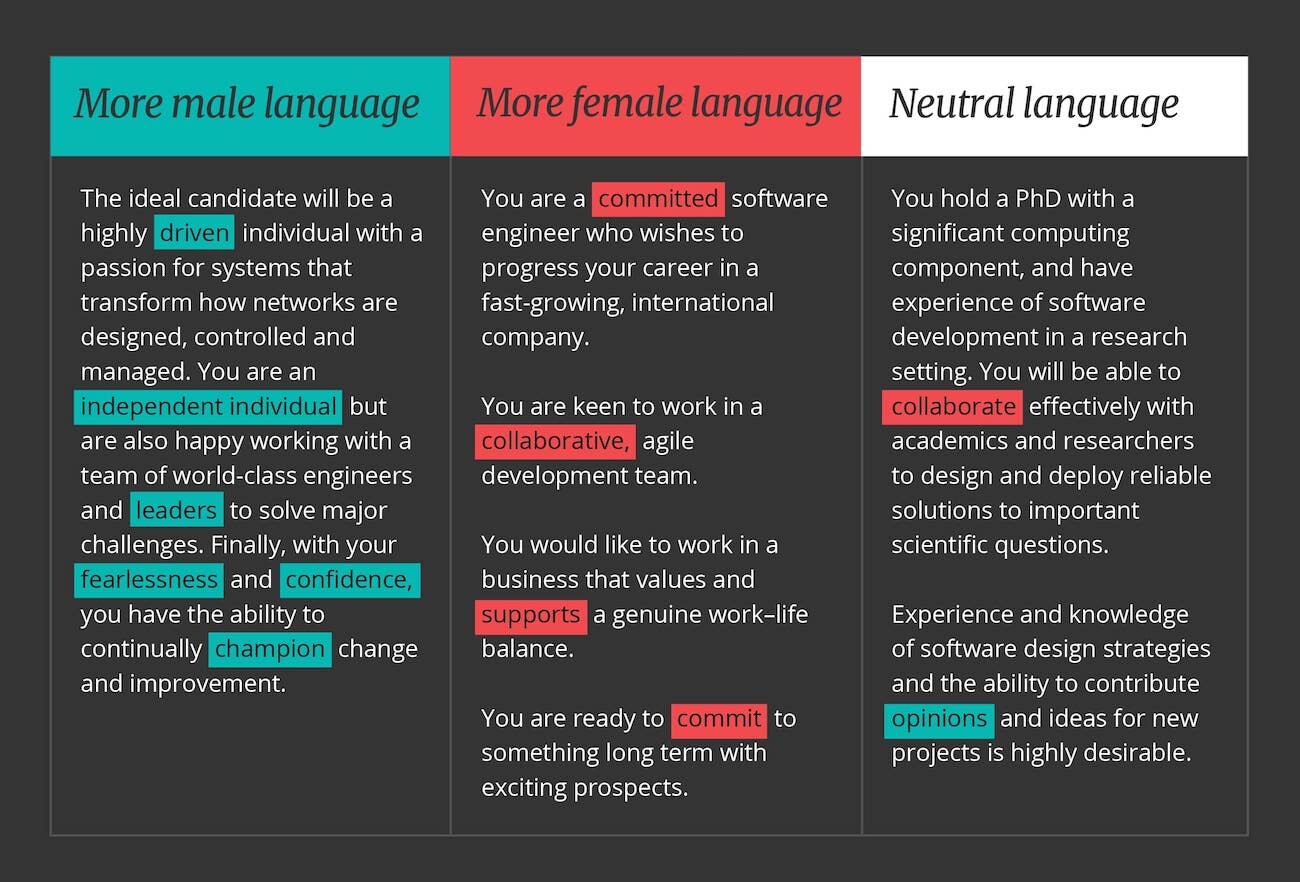

Compare the following table for a sampling of words which research seems to suggest is inherently more appealing to one gender over another:

The theory goes that if the language used in a job application uses heavily male-coded wording, female applicants may feel that the job is not really for them. Let’s see what this might look like by comparing three examples of job adverts: one which uses lots of male language, another which uses more female language, and a third which could be described as neutral (a balance between both kinds of words).

The following samples come from ads studied in our research, although for the sake of anonymity they are not identical to ads online. We have selected the ‘about you’ section by way of comparison:

These examples, based on real-world tech job ads, show how different language can create a different impression of what the job involves and what the working environment would be like. The language in the first advert suggests a fairly competitive, individualistic environment, whereas the language in the second ad seems to suggest a more supportive, friendly atmosphere. The theory goes that the language used in each ad will therefore attract different kinds of people.

Our research: language used in job ads

As we have seen, the kind of language used in job adverts can make them appear more or less attractive to different kinds of people. Consequently, we wanted to explore whether this might have an impact on the kinds of applicants who come forward for jobs at Australian tech companies.

In this section, we delineate our hypothesis and then examine how we conducted the research. In the next section, we analyse the data and, ultimately, we explore what these results mean.

Our hypothesis

To ensure rigour in our research, we began by proposing a hypothesis to be tested:

Women apply to tech jobs in Australia and other anglophone countries less frequently than men because the language used in the job ads is written in such a way that it appeals to men more than women. Because of the masculine language used, women feel less confident applying and so do not.

Our subsequent research was designed to test whether this hypothesis was true or not.

About the research

To address the above hypothesis, we chose to conduct a word analysis of tech job ads to assess how many masculine- or feminine-orientated words were found in each.

Research parameters:

Dates

The study took place in the eight days between 4–12 June 2019. We chose this time frame to give us a snapshot of the job market.

Roles analysed

We selected and analysed job roles which could be described as IT-related, including software development, IT support, IT project management and software design roles. We found these jobs using job boards and by setting up alerts for a range of IT-related job titles. The jobs were selected based on how recently they were posted. They included jobs advertised by a wide range of employers, from international tech companies to small businesses and in-house IT support jobs.

Location of ads

We analysed job postings on the most prominent Australian job sites, including Seek, Indeed, Jora, Careerone and LinkedIn.com.au. We also included an analysis of TechBrain’s job postings within this study to see how our ads measured up against the wider market.

Finally, we chose to include a comparison with IT job postings on a more international level, analysing ads in the US and UK in order to help determine whether there exists a difference in how job ads are written in different countries and whether culture might also influence the language used in this category of ad.

Number of ads analysed

We analysed 1,940 job postings in total, split across three territories:

- 1,740 Australia-based jobs

- 100 US-based jobs

- 100 UK-based jobs

Who conducted the research?

We commissioned an independent researcher to ensure the study was free from bias.

Research tools used:

Once we selected 1,940 relevant job ads, we fed each job role through a free online software called the Gender Decoder for Job Ads . This software analyses job posts to see whether they contain wording that has been shown to appeal more directly to men or women. A full explanation of why some words are categorised as more attractive to men vs. women can be found here.

In total, we included 50 ‘masculine’ words and 50 ‘feminine’ words in our analysis.

In the case of each advert, we counted the number of words that appeal to men and women and collated the data. For adverts which included more masculine than feminine words, we defined these as ‘masculine-coded’. Inversely, ads with more feminine words than masculine were defined as ‘feminine-coded’. Ads which featured an equal number of masculine and feminine words, or none of either, were defined as ‘neutral’.

Analysis of the data

We analysed the data against a number of questions and parameters. The findings are described below.

Masculine vs. feminine words

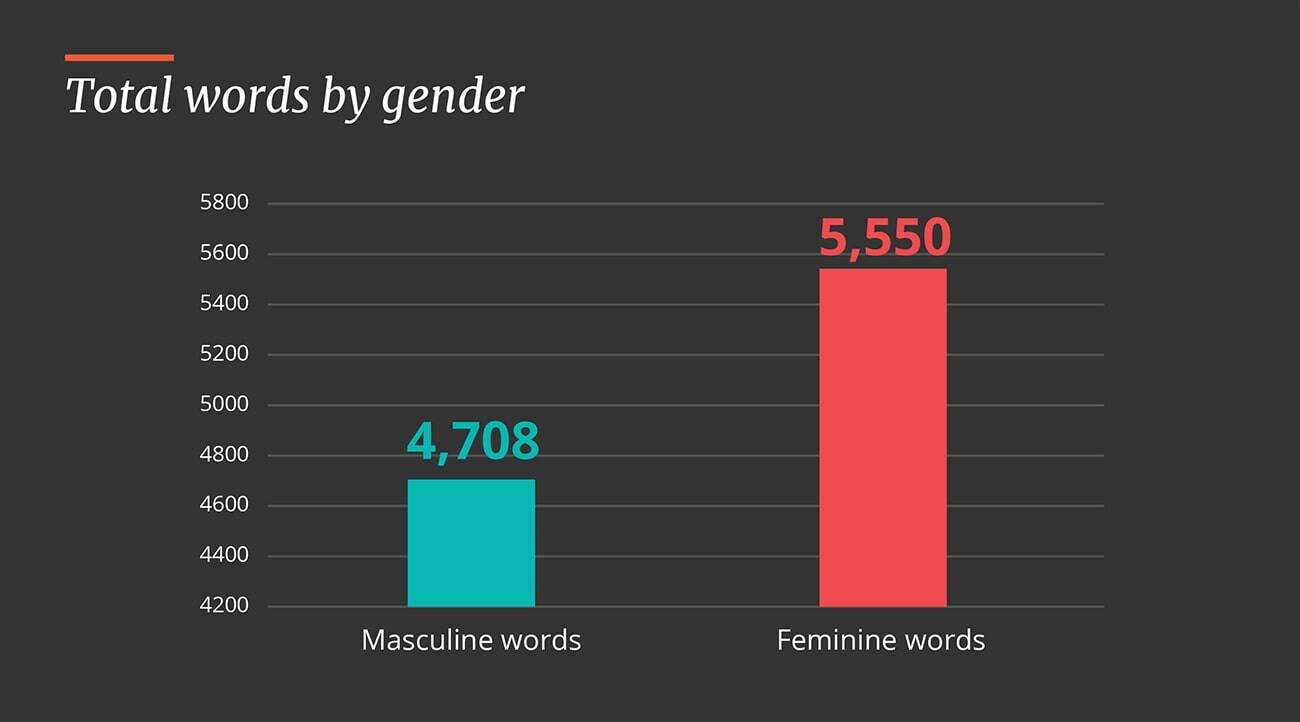

Figure 1:

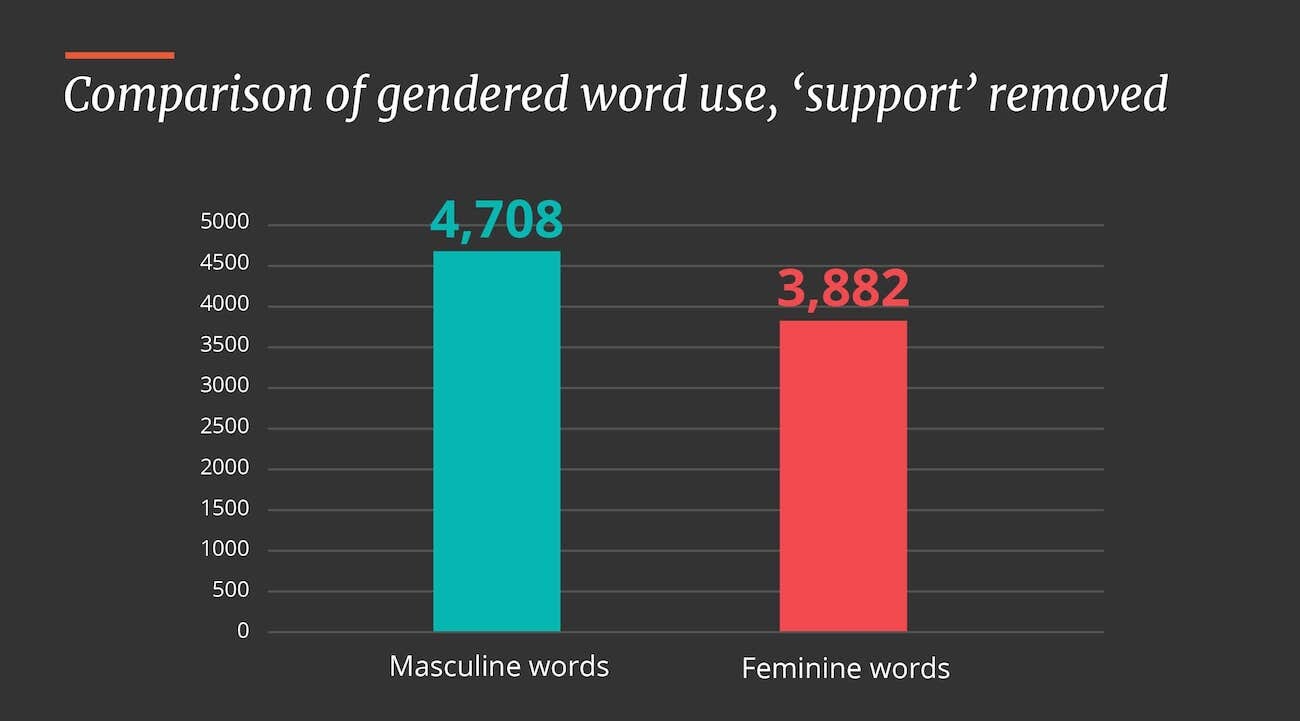

As figure 1 shows, tech job ads in fact use a higher number of feminine-orientated words than masculine ones. There were 4,708 masculine words counted, compared with 5,550 feminine words – approximately 15% more female-orientated words.

Analysis

This suggests that, contrary to our expectations, tech job ads are, in fact, written in a way which appeals more to women than men. So, does this immediately invalidate the hypothesis?

Not necessarily. More research is needed, but there are a number of factors which may have affected the results.

For example, looking at the data, the female word which was by far the most common was the word ‘support’, which appeared 1,668 times in our research. Anyone who works in the IT sector knows just how many jobs include the word ‘support’ in the job title; indeed, IT support staff are found in businesses the world over, troubleshooting, resolving password problems and so on. What’s more, a common task involves supporting software, ensuring it is maintained properly. This means something entirely different to, say, working in a supportive environment.

As a consequence, the word ‘support’, in terms of its technical meaning, might be more common in IT jobs ads than in other fields, be they marketing, sales, operations or anything else. If we were to remove the word ‘support’ from our list of female words, our hypothesis would be supported.

Most common words in tech ads

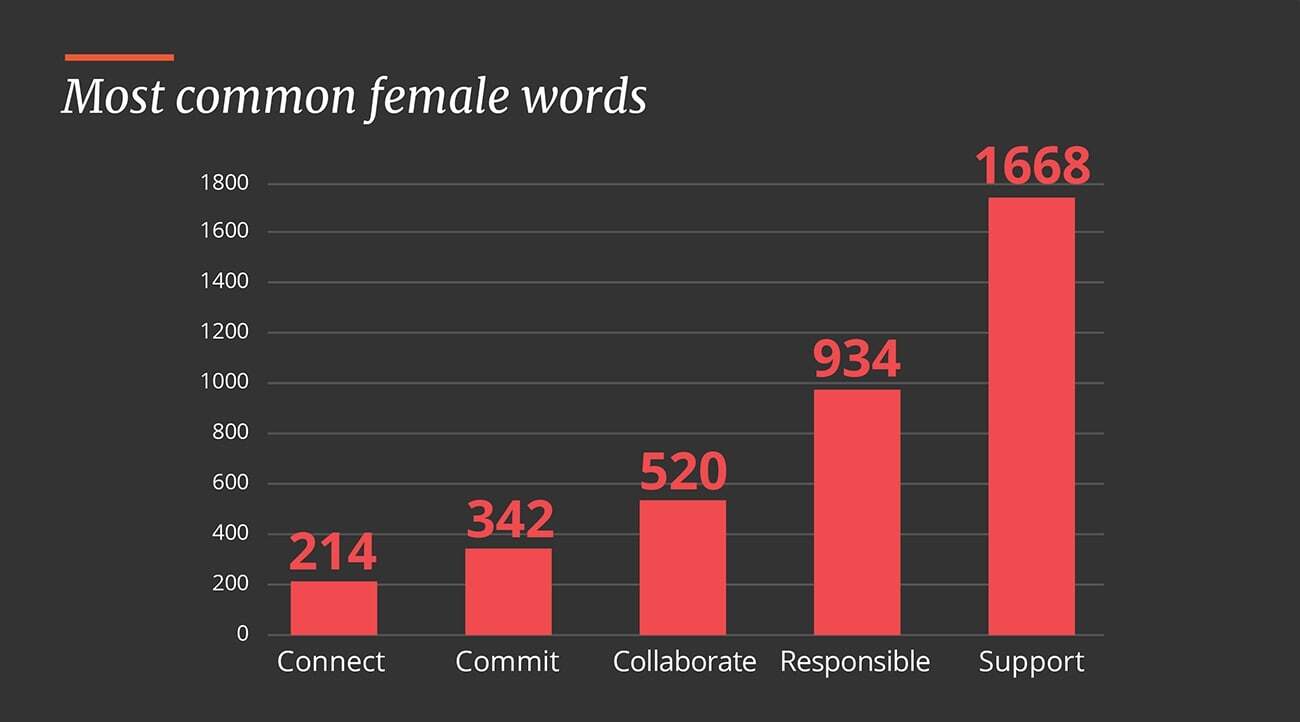

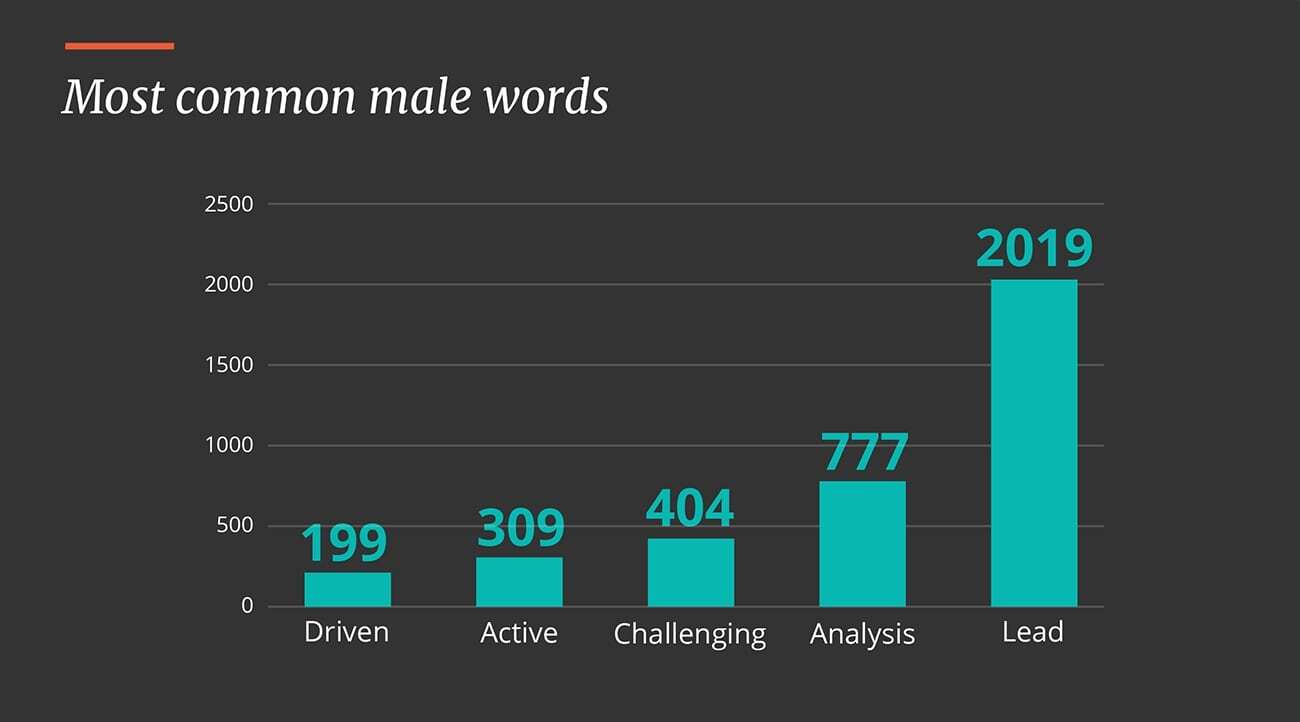

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figures 2 and 3 show the most common words used in the more ‘masculine’ job ads, compared to ads using more ‘feminine’ language.

Analysis

Notwithstanding the issue with the word ‘support’, it’s clear that certain masculine words are found especially often in male-orientated tech ads, with language that emphasises individualistic behaviour, such as ‘leading’ and ‘analysis’. In contrast, the more female-orientated ads repeatedly used more communal words, such as ‘support’ and ‘responsible’.

What this shows is that, when it comes to attracting a wider variety of applicants, there’s certainly value in choosing certain keywords to attract a wider audience. If a company is advertising for a CIO, for instance, they would understandably want to use the word ‘lead’ in the ad text. However, they could balance this with other words designed to make the role feel open to all. For example, the ad could say something like: We are looking for a collaborative and supportive individual to lead our IT department.

Language and salary

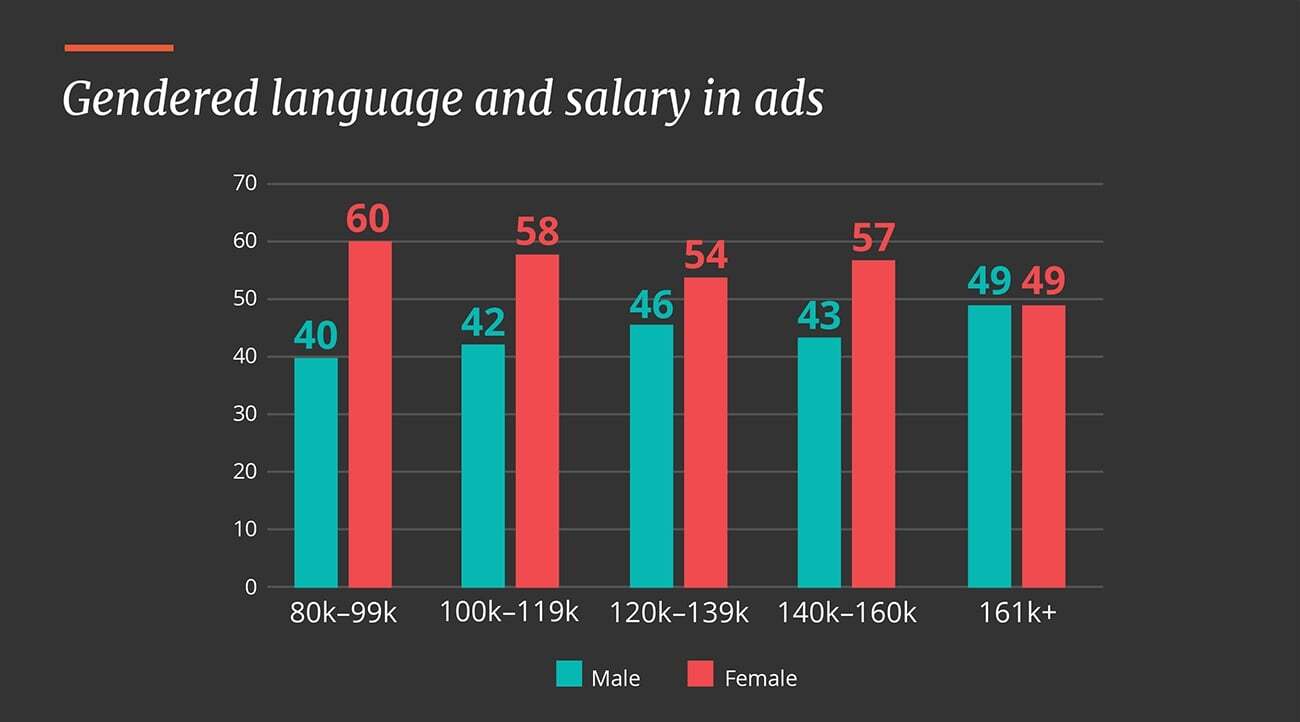

Figure 4:

Increasing the numbers of female employees in technology is all very well, but this does not translate to equality if those women are only taking the lowest-paid jobs. Figure 4 shows how jobs ads with different gendered language were paid in Australian dollars.

Analysis

As we already know, the research indicated that there were in fact significantly more ads which used words that appeal to women than to men. However, when we compare how the jobs in ads with more masculine or feminine language are paid, we notice some interesting trends.

Most significantly, Figure 4 shows that jobs that were the highest paid were also the jobs where most masculine words were used. By comparison, the jobs that were least well paid corresponded to the job adverts where feminine words were used the most.

While more research would be needed to explain this, it does suggest that tech job ads that are written in a way that appeals most to women are also those that offer lower salaries. By contrast, the job adverts that are written in a way which appeals more to men tend to be the best paid.

Difference between countries

Figure 5

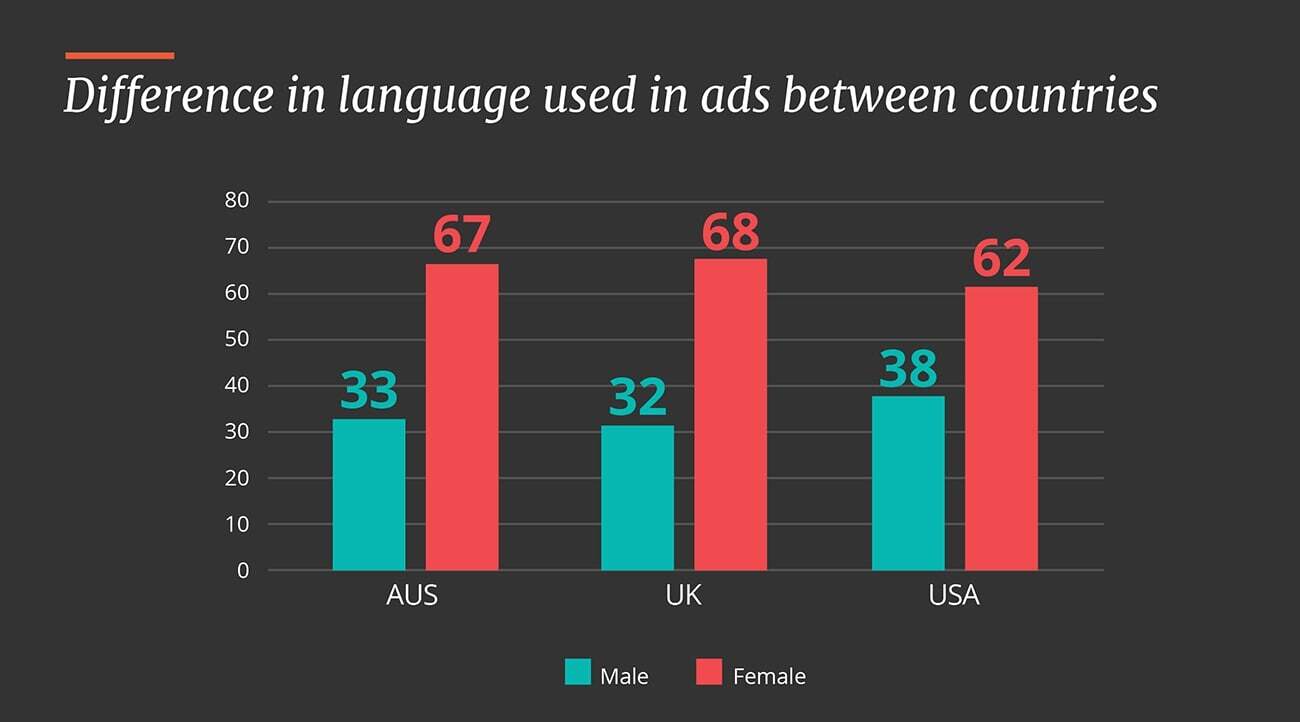

Figure 5 shows how often words that appeal primarily to males vs. females were used in tech job ads in three countries: Australia, the UK and the US. For a balanced comparison, we randomly chose a sample of 100 tech ads in each country.

Analysis

Figure 5 shows that, at least in anglophone job ads, the same tendency we found in Australia is true elsewhere: language which is expected to appeal to women is much more common than language which appeals to men (although of course, the caveat about the word ‘support’ should be noted).

Job ads in the UK use language which would, in theory, be more attractive to women, although there’s only a difference of one word between that country and Australia. Ads in the US were marginally more orientated towards masculine language, although not by a significant amount.

Discussion: how significant is ‘gendered’ language in job ads?

Before discussing the findings in detail, let’s remind ourselves of our hypothesis – the key question we wanted to find the answer to:

Women apply to tech jobs in Australia and other anglophone countries less frequently than men because the language used in the job ads is written in such a way that it appeals to men more than women. Because of the masculine language used, women feel less confident applying and so do not.

With this in mind, what does the research show?

The ‘support’ issue

On first impressions, our hypothesis seems to have been refuted by the data. The research shows that, in fact, tech ads are written with language that should actually encourage women to apply as frequently as, if not more than, men.

Does this mean that tech companies can abandon this as an issue? Since they already writing job ads in such a way that they would appeal to women, surely they have no more responsibility? Not necessarily.

As we postulated in our analysis, the results may have been skewed by the word ‘support’. In other industries, this word in particular may suggest that the employee would be working in a role that supported other employees’ development, helping others work in the best way possible.

By contrast, in the world of IT, the word has a rather different meaning. The word ‘support’ in the context of IT job ads is often a synonym for ‘maintenance’ of a piece of software, and so it frequently turns up in job ads with this specific meaning. Similarly, IT Support is a common job title for a role which involves helping non-technical staff fix IT problems.

As a result, this word appears frequently in IT job ads but does not always carry the same meaning as it might in other industries, say, in a clerical, marketing or accounting position. This means it’s questionable whether it should be included in the analysis at all. And if we were to discount the word ‘support’ from our findings, the results look rather different:

With the word ‘support’ removed, there are in fact more words that appeal to men found in IT job ads. This would therefore seem to support our hypothesis, that IT jobs are in fact written in such a way that they attract men to apply over women.

Of course, a deeper analysis would be required to get a clearer picture of the real state of affairs – our approach only offers a ‘broad brush’ view. Further research would be required to understand how often the word ‘support’ is used as a practical term (i.e., ‘support and maintain software’) compared to its use in a way that appeals to women (i.e., ‘support a great team of developers’).

Pay and gender

Besides the point described above, it’s also especially important to consider the finding about pay and gendered language. As we note in the analysis, jobs that use words that appeal to men – ‘lead’, ‘challenge’, ‘courageous’, ‘objective’, etc. – are especially common in ads for highly paid (and presumably more senior) jobs.

By contrast, words which seem to appeal to women more commonly appear in less well paid or entry-level positions – ‘commit’, ‘depend’, ‘together’, ‘understand’, etc. This suggests that when women do look at IT jobs, the ones advertised with language that they’re most likely to identify with, and see themselves doing, they are jobs that are less well paid.

This suggests that when recruiters in the IT industry write job ads, they regularly use ‘masculine’ words when writing out requirements for more senior roles and more ‘feminine’ language when describing junior positions. This is certainly something that needs to be addressed.

Putting this into context

No one would seriously claim that the only reason there are more men than women in IT in Australia (and elsewhere) is because of the kinds of words used in job ads. It’s clear that there are many other, bigger factors at play – often outside of the industry – from cultural stereotypes to education to the interests and predispositions of males and females to unconscious bias in the hiring process. These factors certainly play a bigger role than the kinds of words used in ads.

Nevertheless, what our research shows is that there is reason to believe that language in tech ads does have at least some effect on whether women feel they can identify with a role and imagine themselves working in that position. For the reasons described above, if we were to remove the word ‘support’ from our results, we find reasonably strong evidence that tech job ads are written in a way that makes women less confident in applying to them.

And, perhaps most importantly, the research shows that the highest-paying, most senior jobs in IT use the most ‘masculine’ language, which serves to only further put off would-be female candidates.

Conclusion: what can we learn from this research?

During the course of our research and analysis a number of conclusions have come to light.

Our key finding was that, contrary to our expectations, ‘feminine’ words were found more often. However, we also noticed that the most frequently occurring feminine word in our data set (‘support’) was possibly skewing the figures, since in the context of IT, this word has a different meaning to what it might mean in other sectors. Bearing this in mind, our research does suggest that, in fact, many IT job descriptions are written in a way that might appeal more to male applicants than to women. If we combine that information with our conversations with women in the technology industry, it becomes clear that yes, the actual words chosen are contributing factor, but also the structure, style and tone of the advert is very important to women applying for roles in the technology sector.

Making sure that job postings emphasise flexible working arrangements, including part-time options and alternate start/finish times to tie in with personal requirements, along with unlimited annual leave, can greatly improve the chances of women applying. Added to which, removing or curtailing long lists of skills and emphasising training or mentoring opportunities will also appeal to female applicants and help to balance the gender divide. These actions aren’t necessarily gendered, rather they project an inclusive working environment for all applicants, leading to more diverse and inclusive teams, which we firmly believe is good for business.

We also uncovered evidence to suggest that higher paid jobs were more masculine in the way they were written. Alongside this, some of the women we talked to suggested that the flexibility required for childcare resulted in lower pay and a more difficult pathway to promotion. While we’re not suggesting that this shows concrete evidence of gender bias, we think it’s worth considering these elements when advertising for higher-paid roles. By addressing the gender imbalance in more senior roles, it follows that working cultures change, meaning that women have a louder voice when it comes to company policy and recruitment.

What actions can IT recruiters and executives responsible for hiring take?

As noted above, no one would seriously claim that the only reason there is a greater percentage of men in IT is because of the language used in job ads. There are a range of factors which influence the number of women who choose IT careers. This is also influenced by our culture and upbringing, historical factors, and education system and university, as well as bias, conscious or unconscious, on the part of employers. It would be unrealistic, and indeed unfair, to put all the blame for the low rates of women in tech squarely at the feet of IT businesses. Nonetheless, recruitment is something we can impact, and the industry can make efforts to ensure its recruitment practices do nothing which would dissuade women from applying to jobs that they are qualified for. In this spirit, see below for some actions that IT recruiters and executives responsible for hiring can take to remove this kind of bias:

1. Pass all your ads through a gendered language test.

There’s no need to remove all words that could be deemed as ‘masculine’. However, it would be valuable for recruiters to ensure that their job descriptions are at least neutral, including a balance of both masculine and feminine language which would make roles feel more appealing and plausible to any gender.

2. Consider the use of words in senior job ads in particular

One of the key findings of our study was that senior, high-paying roles in particular used much more ‘masculine’ language than less well-paid junior roles. Again, aim to use neutral, balanced language that both men and women can identify with.

3. Take an active and conscientious approach to the way you use language when writing job ads

As the findings showed, there are many words which we may unconsciously use that will either encourage or discourage certain kinds of candidates. Recruiters should aim to take a more conscientious approach to how they write these kinds of ads, choosing the most neutral tone and style possible. Similarly, by highlighting company policies like flexible working hours and training opportunities, companies can appeal to working mothers (and fathers) who might otherwise not apply.

4. Avoid ‘cut and paste’ job ads

Where possible, recruiters should aim to avoid simply cutting and pasting older job ads when advertising for new roles – otherwise, you risk continually targeting the same kinds of profile.

There are plenty more things recruiters, and leaders within organisations, can do besides just focusing on word usage – including thinking about where they advertise jobs (are some job boards more male-focused than others, for instance?), doing ‘blind’ application processes, and much more. Being smart about the language, style and tone used in job ads is a good place to start.

Final thoughts

At TechBrain, our culture strongly emphasises the values of transparency and questioning the status quo. We know that the gender imbalance in Australia’s tech industry means the industry doesn’t benefit from as many ideas, talented people and innovators as it should do. While changing the kinds of language used in job ads will not solve the wider problems in society that might put girls and women off a career in tech, it is a place that IT companies can make immediate changes, which is why we now put all of our job ads through a gendered language processor to ensure they use the most neutral language possible. We’re also pledging, as a result of this research, to highlight our flexible working culture in an attempt to encourage applicants with children or other dependents to come forward.

We believe our research reveals some valuable trends in the way Australian tech jobs are advertised and that it can help our peers do a better job of hiring a more diverse workforce, so we challenge them – and ourselves – to make a difference in hiring processes by using more balanced, neutral and welcoming language.